With the forecast looking bleakly British for a few days, glorious some others, we decide to save the glorious days for a wine tour and trip to the seaside city of Valparaiso. The others we’ll spend doing a city tour, trying to find me some warm clothes, going to the cinema, to the Human Rights museum, and picking up some boots Vivo has amazingly shipped out to Chile for me. This post will be largely about our week in the city, with our adventures out saved for separate entries.

I should caveat this post especially that the information shared in any of these posts is based on brief moments of learning, that will clearly be biased from the perspectives of those who share the knowledge we share with you. No doubt there is more information on all sides. These posts hopefully serve as inspiration to learn more, rather than to infer what we say here is the only story to be told.

Our first morning in our new flat for the week is spent with James getting food in, whilst I get planning. There’s a free walking tour this afternoon, and we decide it’ll be a perfect way to get to know the city that I’d been previously told had no tourist attractions.

A Brief History

We find our guide MJ at the Plaza de Armas, a young Colombian woman who rattles off her knowledge of Santiago like the pro she is. We find this really hard to follow at first, despite her favourite question of “got it?”, like a YouTube video spliced together without a pause to even process the last few seconds. We feel old. Thankfully, we either get used to this continuois influx of info, or the amount slows down to more manageable chunks, and we get into the rhythm of learning.

We first learn about the Plaza de Armas that we’re standing in. She points out that you find Plaza de Armas in almost all Spanish cities, that this is a distinctly Spanish thing. You don’t get them in Portuguese settlements, and sure you get main squares in other cultures, but there is something distinctly Spanish about a Plaza de Armas. The history of this one is this is where Pedro de Valdivia decided to found the city of Santiago del Nuevo Extremo.

The city was defined by the Mapocho river to the north, Cañada (an offshoot from the Mapocho), the Andes and Santa Lucia hill to the east (photo below), and another mountain range to the west. The snow tells you which one is the Andes if you ever get turned around.

Of course, Valdivia wasn’t the first one here. The native Mapuche people were already here, living their best lives. Their culture was distinct from the Inca empire, although they existed at the same time. Unlike the Inca empire, the Mapuche don’t have a hierarchical structure running across their towns and villages. MJ tells us that when the Inca empire tried to expand south, the majority died on the way, due to the extreme climate of South Peru and North Chile that we’d just left behind. But some made it through, and when they met the Mapuche, they didn’t believe they had come from the north. For the Mapuche, water equates to life, and they know there is no water above the Mapocho river. Therefore, there can be no life. The surviving empire explorers manage to convince them, and they extend an ‘Inca trail’ to be able to trade and connect. I later find out that the Inca empire did try and take over the Mapuche like they did so many other cultures, but the Mapuche were having none of it and (I think) may be the only culture to withstand an Inca takeover.

So, when the Spaniards arrive to plonk their flag in the ground, this isn’t the Mapuche’s first rodeo. MJ tells us that they pretended to be on board with these new people, but when the weather changed, and the Spaniards had no clue how to survive in the now vastly different climate, the Mapuche did the equivalent of shrugged and walked away. I later find out the Mapuche continue to create problems for the Spaniards, fighting and beating a weakly provisioned and captained Spanish side (there’s no gold down here so Spain only sent their C team). Sadly, the current situation for the Mapuche people mimics so much of other cultures who faced colonialism, and it’s become an incredibly complex subject. Nevertheless, the Mapuche flag flies pride of place next to the Chilean flag on the government building on the square, and we see much support and reference to this culture throughout our time here.

We learn about a huge earthquake that destroyed 70% of the city. That there was a big hotel for diplomats on the main square that was converted to a fire station in honour of a tragedy that killed a bunch of people when a huge fire burnt down a government building. That Congress was moved to Valparaiso to create some distance and avoid corruption. That the animals on the crest of the flag are a condor and a vicuña (a wild, roaming camelid similar to a llama), see top of the building below that used to house Congress:

And that there were two important men in Chilean history called Montt and Varas, and this is why these are prominent names of other cities in Chile:

We move along down to the Presidential Palace, La Moneda, where you’d be hard pressed to not know which country you’re in.

Apparently each flag represents the 14 regions, and there’s a statue for each president they’ve had in office going around the block. MJ is at pains to say she does not want to go too much into the recent political history here as it’s a contentious subject. There’s a lot of posters marking 50 years since Pinochet overthrew the government, and also an array of placards with the photos of victims of police brutality out front from a previous protest. These weren’t murders from Pinochet’s time however, but more recent history. Really sad.

MJ steers us away from the complex and contentious more recent history, to go back to the history of the country. Bernardo O’Higgins liberates the country from Spanish rule and designs the flag. The white represents the Andes, the blue represents the sea, the red represents the Chilean flower and the blood that was spilt in the fight for independence, with the star signifying the union of regions to one country.

We head to santiago’s ‘Wall Street’:

We learn some more random tidbits, like Lapis Lazuli can only be found in Chile and Afghanistan. That 30% of the world’s copper comes from Chile. 53% of the world’s lithium reserves come from Chile, Peru and Bolivia. What’s happening in Chile (and probably across the world) with lithium is a sorry state of affairs that just seems to be a replay of the abuses of the past, but with a different mineral, we’ve learnt nothing.

San Cristobal hill is actually a dormant volcano. And that Chile (and arguably Peru?) is ethnically more homogenous (compared to Brasil and the Caribbean coast of Latin America) because, without the Panama Canal, the Spanish shippers just couldn’t afford or didn’t want to risk shipping slaves around the Magallen strait to get them to the west coast.

We try some peach drink called Mote con Huesillos that looks like the teeth of all the people who drink it at the bottom, but is actually wheat soaked in this peach pit drink. The liquid is fine for me, but the wheat is a weird texture I don’t get on board with.

We end with a highly graffiti’d statue we had come across on our failed first day in Santiago, and MJ explains it was a gift from Germany to say thanks for looking after her refugees after the war. The ‘open secret’ is apparently that those ‘refugees’ were largely nazis, and that they helped to inform the horrendous actions of the Pinochet government (hence the graffiti). I don’t know if the timelines necessary match up with that theory, but I can say that what I later learn about what happened under Pinochet’s rule was horribly reminiscent of what the Nazis did.

And that was the walking tour. As it was Halloween, and not a pumpkin to be found anywhere, James spent the evening making a special, spooky meal, inspired by meals his mum made when growing up. It was a fantastic way to mark the day and bring a bit of levity to a difficult few days.

Unfortunately an undercooked sausage continues to haunt James the next day, and he’s back in bed fighting off his latest internal fight against something foreign. It’s nothing like in La Paz at least, and he orders me to still go ahead with my day (so long as I get him a giant Gatorade and box of crackers first).

Museum of Memory and Human Rights

The plan for the next day was to avoid the crummy weather by hiding out at the Museum of Human Rights. This means me getting to grips with the metro which is amazingly quiet due to the national holiday in place for the day of the dead. The museum is equally quiet as I jump onto an English tour.

It’s a difficult museum to go around, and at one point I feel a bit faint, so there’s a chunk I missed as I regained my composure. The museum was founded specifically to call attention to and acknowledge the human rights abuses of the Pinochet regime, in a bid to make sure it never happens again. It’s a bold statement, and another example of a country owning a part of its terrible history. Not writing it out of the history books and pretending it never happened. Well at least, not anymore.

For those like me who know nothing of this era, I’ll recount what I learnt and can remember, but it’s definitely worth learning more about. As my tour guide says, the important thing here is to provide evidence to counter any claims that this era wasn’t as bad as it is made out, was a necessary evil, or just didn’t happen at all. (Sound familiar?)

I’ve subsequently watched a good Khan Academy video on this time period, so the information here will be a mixture of the two. We begin with the overthrow of Allende, the democratically elected President of the country three years prior. Allende was a leftist, and his presidency was mired by failed economic policy. The USA, in the midst of the Cold War, is none too happy about the growing lefty governments in Latin America, and there will be forever debates over wether the failing policies were due to the USA making Allende’s job impossible to destabilise his presidency, or they were just poor policies on their own. As with a lot of this, we will likely never know.

There are declassified documents from the CIA saying they were finding out the likelihood of a coup to get our man out of power. Whether or not they orchestrated said coup, again, is up for debate, but there’s evidence they were asking the question.

Pinochet and a the other heads of the military divisions stage said coup on September 11th 1973. They bomb the presidential Palace and offer Allende a flight out. You can’t blame the man for not taking up said flight after just being bombed by his own men. One way or another, Allende ends up dead. Some say they saw him kill himself. Others say they were part of the group that shot him. Again, we will never know, but the outcome is the same, there is now military rule.

They round up all the opposition and put them in the National Stadium as a makeshift prison. This is the beginning of an ever worsening situation. The coup, that started with the combined military leaders taking over due to perceived lack of confidence in the Allende leadership, leads to Pinochet taking full power a year later, including over his coup-pals.

The museum shows us the various tactics the Pinochet government used to maintain power over the next 15 years. As I said previously, a lot seems sadly familiar. Having recently finished First They Killed My Father, this also feels sadly reminiscent of the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia too.

One tactic is to instill a bunch of rules, that are indiscriminate, and take rights away from the people. If you are deemed to have broken the rule, the military have the right to do what they want with you. After all, the judicial arm of the government no longer exists, there are no trials or rights. The military has final say. One such rule invoked is banning people being able to meet in groups, this includes sports clubs and neighbourhood watches. Our guide explains this serves two purposes. To not just stop any counter-groups spreading their message, but to break down communities, to isolate people from one another. If you don’t know your neighbour, will you care that they disappeared in the night? Or that they are starving? Will you speak up and help them if you don’t know them to realise they are innocent? Alongside the other rules, this helps to breed distrust of one another, because you don’t want to get caught up with the wrong person and get disappeared for just associating with them.

This tactic of isolation is fascinating, because it shows how a nation of a culture of individualism is actually weaker, than a culture of collectivism, who will empathise and fight and help one another. They’re harder to rule, and so this breaking down of communities is key to making a people easier to control.

The other tactic is to take over the media, rewrite history and the education system. Including burning books and removing all art and expressionism. Any book that they think may be left-leaning gets burnt, going so far as to burn books on Cubism because it looked like Cuba. Murals, posters and walls are painted over. If you happened to have any said material that could be construed as against the current regime, well you were going to experience their other main tactic, torture and murder.

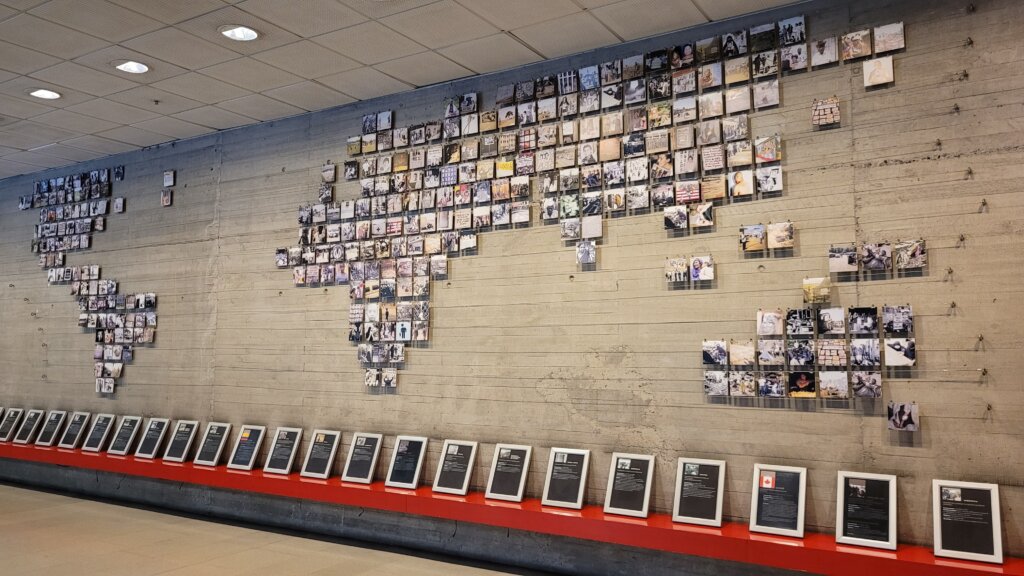

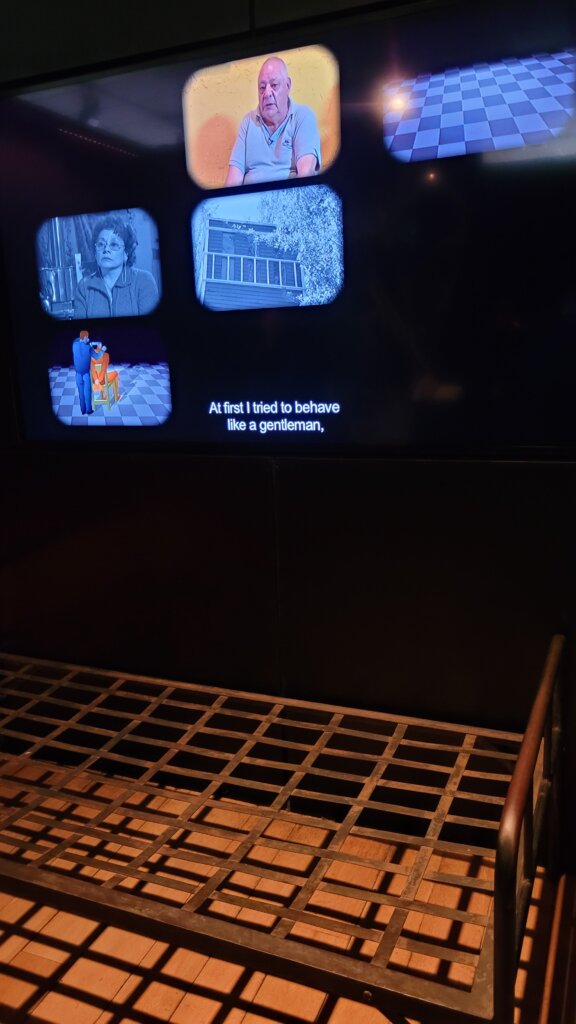

A secret police is set up a la the SS and KGB. Of course, some of the people taken away are part of the opposition, but also included are completely innocent people. They aren’t even interrogated, after all, they have no reason to be there, they are just tortured. There is a whole video of victims here talking of their experiences. Some speak to the torture being less about the physical experience (which also sounded horrendous), but the worst part being the psychological wounds they carry from it. The powerlessness. That the aim was to make them feel inhuman and worthless. If you were lucky, you got to go home. But thousands disappeared. Of course, the tactic here wasn’t just about getting information, but to show the unimpeachable power of the regime, to create fear, to stop even the thought of rising up. There were over 1000 torture centres all across the country, from all the way in the North, down to the furthest south. This wasn’t something for the city, this was everywhere. You couldn’t hide. Here’s a map of each centre:

The international community apparently raise concerns about Pinochet staying in power without being democratically elected. This causes the regime to find a way to make the regime legitimate on the international stage. They do this through a plebiscite, whose result is in his favour, and ignoring the fact there is no official electoral roll to ensure there’s no forged votes. The previous secret police is closed down, and they create a new one, to throw off the beedy eyes of the foreigners.

With control of the narrative through the media, they rewrote history, they dehumanised the people they persecuted, and they fabricated stories of the disappeared. One woman who is taken by the regime is found beaten and dead in a river. The newspaper reads how it was femicide by a lover. The loved ones of the disappeared are told that they must have fled the country of their own accord. Even when you know this isn’t true, how do you argue? There is no law and order. There is threat of the same happening to you. There is no community to trust to support you. You are powerless to counter their lies of your loved one. They also fabricate a plan by the Allende government, a whole book is written and made up to show people the Allende government was not what they said they were. The author later admits this, but defends that it surely did exist, they just never found it, so he made it real.

If this is all starting to feel like a familiar amalgamation of the worst regimes, dystopian novels, and tactics still used to this day, then you’re on the money, and why this museum sees its importance to exist. Whilst Pinochet is in power, and the people live in fear, at the beginning, the economy is going strong and doing extremely well. As with before, there are debates as to whether the reason he did so well was because the USA were backing this horse, or because his policies were actually good. And this, I believe is where things get contentious, because of the three lies that permeate. That either this didn’t happen, that it didn’t happen as badly as it’s said, or that it needed to happen for the good that came from it (an argument I’ve heard in Peru too). The last is the most concerning, as it’s seemingly too easy for those that benefit from crimes against humanity to say it had to be done, or it was necessary. No crime against humanity is worth a good economy. A wall to the lost:

The other really troubling part of the whole story is yet another example of the complete manipulation and indiscriminate fuckery (for want of a better word) of the USA’s Operation Condor, to crush left uprisings around Latin America during the Cold War. America apparently only stopped backing their poison horse Pinochet when the regime’s secret police ends up bombing a target on USA soil with a US citizen in the car. As our guide says, it’s fine for the USA to get involved with the killings and torture of another nation, but when one of their own gets in the crossfire and it’s on their turf, well that’s not on. This is all in declassified documents, it’s not conjecture.

The end to the regime comes from a plebiscite, that was on the cards from the previously forged 1980 plebiscite that said there would be another in 1988. It seemed that by this point, his pals had had enough. Pinochet thought he would win, and didn’t fake the result this time for whatever reason. There’s evidence he was going to overrule the outcome if it didn’t go his way (sound familiar), but his pals don’t support him on this, and neither do the USA. It seems everyone, but him, has had enough, and he loses his almighty power, but remains in a military position for almost 10 years more. He eventually gets charged with crimes against humanity in the 2000s, but after 4 years of no progress, he dies of natural causes, seemingly never facing any consequence for the suffering he ruled over.

After this mentally and physically chilling experience (the museum is freezing!) I take a quick wonder about Barrio Yungay, but it’s freezing, I don’t feel too safe in this ‘seen better days’ district for whatever reason, and head back to check on James.

Another Side to Santiago

The rest of our time in Santiago is spent (not in this order) climbing up San Cristobal hill to take in the sunset, which is stunning. The view here alone is amazing, being able to take in the whole city, and the glorious white-capped Andes to the west. It’s a far cry from the view over Cusco:

We walk in torrential rain to get to a cinema to see Killers of the Flower Moon, our first film since leaving the UK. Collecting my Vivo boots from a colleague of my mum’s, going shopping in the fancy part of town to return and buy new jeans, despair at the lack of jumpers anywhere and giving in to buying a men’s mustard coloured sweater in desperation.

Having spent almost our whole time in Santiago down in Central Santiago that is bohemian, covered in graffiti, often falling into disrepair (not dissimilar to Barranco in Lima), surrounded by edgy rockers, skaters, cool uni students:

Our trip up to the east of Cerro San Cristobal is like a different city:

Black puffers and gilets, blue suits, starched shirts, rich folks with tiny dogs, abound. There are no tattoo’d, edgy uni students here. The streets are free of graffiti. The eateries are wide, clean, ordered. It looks like San Isidro in Lima, as do the people. I’m glad we got to see this side to Santiago, because up to this point, I had genuinely looked at the demographics of the country wondering if there were any older people! That they live such disparate lives I think reflects the disparities of the country at the moment, and the difficulty they are facing politically, between an outspoken and empowered youth movement, and the other side who I believe are more Conservative and look down on the youth playing teenage anarchy. “You haven’t experienced Chile if you didn’t experience a protest” as our guide MJ told us, and she’s not wrong. But it’s a fundamental right I’m glad to see the youth making the most of, after all, remember where this country was less than 50 years ago. The right to protest is something we need to be protecting in the UK, and it worries me which way our own government seems to be going. So keep protesting Chile. Never stop making yourselves heard!

The other key aspect of any city for us is of food. The prevalent memory is just how much more expensive it is compared to London! But of what is Chilean cuisine? I’m told by a Chilean that we have to try a specific item from a specific place, so we do as we’re told. A Luco from Dominó, and we get given what is essentially a frankfurter covered in cheese:

Now I like a hotdog as much as the next person, but the obsession with the hotdog here is amazing, and probably tells you enough about the quality of Chilean food without me saying anymore. There are places that sell about 20 variations of toppings, with 3-6 different types of dogs. It’s a matrix table I could not get my head around. The hotdogs are good, I’ll give them that, but how I miss Peruvian cuisine (and Peruvian prices)! (In their defence, the pastel de choclo and empanadas are also apparently a delicacy, but we tried neither).

Our Last Day

On our last day we finally do the task we set out to do on day one, changing pesos to USD so we can take some over to Argentina and make the most of the “blue dollar rate”. I also manage to donate my ‘old’ Vivo boots to a church. We spend the day eating up our food resulting in a breakfast of porridge and icecream, and lunch consisting of pasta, peas, omelette with green pepper, carrot sticks with cheese, cheese on toast, and crisps. Living the dream. Then pack up and head out for a drink to kill time before spending the night at the airport for our 4am flight.

As we wander about, we hear the familiar call of football on TV again, this time it’s the Copa libertadores final between Argentina’s Boca, and Brasil’s Fluminense, but more importantly, they have beer for £2. The game is a blinder, including a bitch slap and comedic fall to the floor. The owner has clearly been having day of it and ends up slumped in the chair inside snoozing through the gripping extra time:

The game over, we go for a Chinese dinner and learn that beansprouts translate to Dragon’s Tooth. Very different vibe! And then we’re off to the airport to ‘sleep’ and fly the final distance to the snowy end of Chile. Thanks to the help and kindness of strangers (and a Boca fan), we make it there in one piece.

Nothing to See Here

Whilst I’ll never be glad to have not made it to Mendoza, I am glad to have been able to give Santiago another chance. By the end, it was really growing on me. There was just enough order and westernisation to not feel completely out of place, but also just enough vibrancy, latin and indigenous history to feel the energy and liveliness of a Latin American city. Unfortunately, we did get a few warnings of unsafe neighbourhoods, and crime is apparently on the rise here (as in most cities it seems). This, alongside the ridiculous cost of food (and the food really not being great for what you pay for), were really the only main drawbacks of being here. The highlights were the views of snow-capped mountains, glorious green hills in the middle of the city, vineyards of easy access, and cheap public transport, make Santiago now up at the top end of my favourite cities list. So, thank you Santiago, I’m glad I got a second chance to know you.

**********

Adventure – trying mote con huesillos, getting up Cerro San Cristobal after a long vineyard day, exploring the different areas of Santiago (and being warned off some of them) by bus and metro.

Excitement – being able to take public transport, and for 80p a go, bus or metro combined! Finding out our cheap Airbnb had a pool, gym and laundry, spontaneous purchases of the yummiest chocolate éclairs from the shop under our flat, finding tres leches ice cream.

Trauma – haunted sausages, supermarket prices, being on edge on the metro thanks to many reports of pickpocketing but having no issues ourselves, trying to get coins for the laundry, finding ourselves at odds with other on more than one occasion.